Memorial - Silver Queen II – the first aeroplane flight into Zimbabwe

Fairbridge Way and Albemarle Road / Winnie’s

Way

How to get there:

On the Corner of Fairbridge Way and Albemarle Road / Winnie’s Way,

Bulawayo. The NMMZ plaque is in a small patch of rough ground sectioned

off from the golf course a few yards from the road.

The

unsuccessful take-off on 6th

March 1920 where excited crowds thronged the race course which was to be

used as a landing ground.

The story of the first flight into the country is very exciting and must

have featured prominently in Rover, Hotspur, The Magnet and Wizard, the

most popular of boy’s comics being read in 1918.

The Monument plaque reads as follows: The first aircraft to reach this

country, the Silver Queen, a Vickers Vimy bomber, crashed near this

place on 6th March 1920. The aircraft was flown by Lieut-Col Pierre van

Ryneveld DSO, MC and Flight Lieut. Quinton Brand DSO, DFC. The other

members of the crew were Mr FW Sherratt, an engineer from Rolls Royce

and Flight Sgt Newman (RAF) an airframe engineer.

This was the first flight from London to the Cape. Silver Queen I After

the crash and some days later the flight was continued and completed by

van Ryneveld and Brand in a DH9 aircraft named Voortrekker. All the

other challengers that started from England abandoned their flights. The

De Havilland machine piloted by Lieutenant Cotton, of Australia, smashed

its tail and three wings; Major Bradeley's Handley-Page crashed near

Atbara, while Major Welsh's Royal Force machine was forced to descend in

a damaged state at Koroska. The Times Vickers Vimy bomber crashed at

Abercorn and was smashed beyond repair.

By 1918, British aircraft were capable of carrying a fair load in

addition to their crew and the British Air Ministry decided to make

several long-distance flights to pave the way for civil aviation which

would follow when peace returned to the world. A Handley-Page bomber had

already, in July 1918, flown from England to Cairo via Paris and Rome,

and in November the same aircraft made the first flight from Egypt to

India.

It was decided to open up the air route from Cairo to the Cape, and in

December 1918 three survey and construction parties were appointed to

establish landing grounds at convenient intervals along the route. No. 1

Party was responsible for the sector from Cairo to Nimule (Sudan), No. 2

Party for Nimule to Abercorn, and No. 3 Party, commanded by Major

Chaplin Court Treatt, for the sector from Abercorn to Broken Hill and

thence down the railway line to Cape Town.

Despite these obstacles, and numerous other hardships and hazards -

including communications and transport difficulties, mosquitoes and

tsetse flies, lions and other animals and reptiles - the task of the

three survey parties was completed within 12 months, and at the end of

December 1919, the Air Ministry declared the Cairo-Cape air route open

with 24 aerodrome and 19 emergency landing strips fit for use.

Soon after this announcement several expeditions declared their

intention to set out for the Cape. First, on Saturday, January 24 1920,

was a converted Vickers Vimy bomber, sponsored by The Times of London.

Within the next 10 days three more aircraft left England - a

Handley-Page sponsored by the Daily Telegraph, a DH14 of Airco Ltd

(neither of which got very far), and a second Vickers Vimy named the

Silver Queen I.

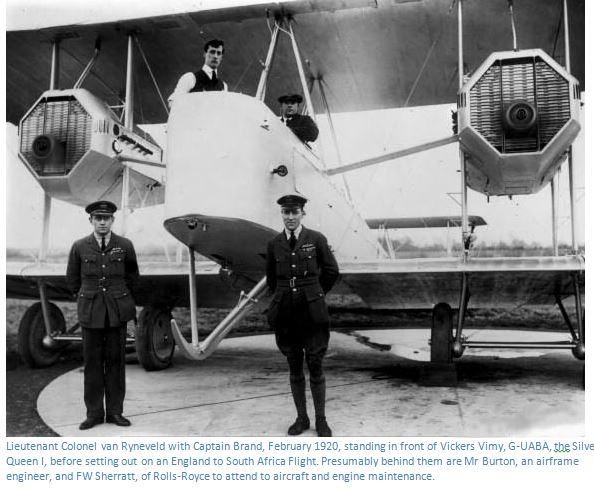

Silver Queen I was sponsored by the Government of South Africa as

General Smuts wanted South Africans to be the first and authorised the

purchase of a Vickers Vimy, G-UABA, for £4,500. She was flown by two

South African pilots, Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre van Ryneveld, DSO, M.C.,

and Flight-Lieutenant CJ Quintin Brand, DSO, MC, DFC. With them, to

attend to aircraft and engine maintenance were a Mr Burton, an airframe

engineer, and FW Sherratt, of Rolls-Royce.

The Times Vimy, after a relatively trouble-free flight across Europe

arrived at Heliopolis, near Cairo, on Tuesday, February 3, and departed

for Luxor on the following Friday. From then on the expedition was

plagued with mechanical trouble as their water-cooled engines overheated

and developed serious leaks. Time and again during the following three

weeks they were forced to land to rectify the defects, but they pressed

on; the crew must have been possessed of iron determination to have kept

going under such strenuous circumstances, they arrived at Tabora in

central Tanganyika on Thursday, February 26, and more will be heard of

them later.

Lieutenant Colonel van Ryneveld with Captain Brand, February 1920,

standing in front of Vickers Vimy, G-UABA, the Silver Queen I, before

setting out on an England to South Africa Flight. Presumably behind them

are Mr Burton, an airframe engineer, and FW Sherratt, of Rolls-Royce to

attend to aircraft and engine maintenance.

Silver Queen took off from Brooklands on Wednesday, February 4 and

before leaving, Van Ryneveld declared that they intended to reach Cape

Town in "the shortest time that circumstances would permit" and that

they would do their best to overtake The Times expedition. Their flight

across Europe to Gioja del Colli in southern Italy was more or less

incident-free, and after refuelling there they took off for Derna in

Cyrenaica.

This flight, made in atrocious weather, was the first non-stop air

crossing of the Mediterranean from Italy to North Africa. Later one of

the pilots remarked that it had been "an unforgettable nightmare ... an

ugly impression which they would like to obliterate from their minds".

The Rhodesia Herald, in an editorial on February 18, 1920, wrote: "Their

grit and stamina were put to the severest test in that terrible voyage

across the Mediterranean ... their 11-hour struggle against adverse

atmospheric conditions will live in aviation history ... as one of the

most noteworthy achievements."

Despite this ordeal they spent only one hour at Derna and then took off

for Sollum where, upon landing, the aircraft's tail was damaged by a

boulder. Ford car parts were adapted and after a two-day delay they left

for Heliopolis, which was reached on the evening of February 9.

The following day, Silver Queen I took off from Heliopolis and flew into

the night, heading south. All went well for the first few hours, but

then a draining tap on the radiator of the starboard engine vibrated to

the open position, allowing all the cooling water to escape and the

engine overheated. They were committed to an immediate forced landing in

pitch darkness near Kurusku, about 80 miles (128km) north of Wadi Halfa.

Upon landing, the aircraft ran into a pile of large boulders and the

fuselage was irreparably damaged, but the crew miraculously escaped

serious injury.

The engines were apparently undamaged, so the crew removed them and

transported them back to Cairo by boat and train. After tests, the

engines were fitted into a second Vimy provided by the Royal Air Force,

at the request of the South African Government. Mechanic Burton now

stood down and was replaced by Flight-Sergeant EF Newman of the Royal

Air Force.

Silver Queen II left Heliopolis early on Sunday, February 22, and

reached Wadi Halfa that afternoon. Here a careless mistake, in which a

fuel tank was inadvertently filled with water, meant it became necessary

to drain the entire fuel system. The crew's remarks do not appear to be

on record!

Some engine trouble was encountered on the flight, but this was repaired

at Khartoum; thereafter the journey was uneventful for the next few

hundred miles and at 1.45pm on Thursday, February 26, they landed at

Kisumu on Lake Victoria, from which The Times Vimy had taken off that

morning.

Silver Queen II left Kisumu early next day with the intention of flying

non-stop to Abercorn, but engine trouble forced them to divert to

Shirati on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria (near the Kenya /

Tanganyika border), and they spent the rest of the day working on the

engine. That same morning, February 27, the Times Vimy took off from

Tabora and within minutes was obliged to return due to engine trouble.

The distance between Shirati and Tabora being about 300 miles, the

position at mid-morning was that little more than three hours of Vimy

flying time separated the two expeditions.

After working on the engines all morning The Times Vimy crew boarded

their aircraft to depart for Abercorn, but this time the starboard

engine failed completely on take-off. The aircraft swerved into the

bush, was wrecked beyond repair, and the flight had to be abandoned.

According to reports: "some regrettable language was used".

Silver Queen II, her engine defects rectified, left Shirati early on

February 28 and, overflying Tabora, landed at Abercorn, the crew

reporting having sighted the aerodrome at Tabora, but "no sign of The

Times machine".

Abercorn being 5,400 feet above sea level and the airfield none too

large, the pilots made the prudent decision to lighten the aircraft's

burden by offloading what they described as "an enormous quantity of

spares and ... much of our own kit, flying boots, etc.” They also

revised their plan to fly direct to Broken Hill and decided instead to

make for the landing ground at Ndola which, being nearer, would require

less fuel and so further lighten the machine for its take-off from

Abercorn.

Having thus re-organised the loading of the aircraft, they took off for

Ndola on Sunday, February 29. The Abercorn-Ndola route has few

geographical features, and severe test of their navigational skills.

Their navigation aids consisted of a magnetic compass and a map (almost

certainly small scale with little detail) In addition, serious trouble

developed in the starboard engine, and they began to contemplate the

possibility of landing in the bush, but then, as the Livingstone Mail

put it, "happily the engine recovered sufficiently to bring the machine

to Ndola", where they landed, probably with considerable relief.

Heavy rain fell the next day delaying their departure until Tuesday,

March 2nd when they took off and landed at Broken Hill. After refuelling

they left for Livingstone following the “iron compass” of the railway.

Excited railway officials at isolated stations and sidings kept the

station-master at Livingstone informed of the aircraft’s progress by

means of the railway telegraph…Lusaka 11:00…Kafue 11:38…Mazabuka

12:05…Kalomo 1:40…Zimba 2:20 and then, after circling the Victoria

Falls, “Silver Queen II” touched down at Livingstone at 2:42pm.

Heavy rain fell on Tuesday night and the airmen had to postpone their

departure until Thursday, but engine trouble meant they did not leave

until Friday morning when a stiff south-easterly wind was blowing and

progress was slow, at times their ground speed was less than 60mph.

Wankie 9:40…Dett 10:20…Ngamo 11:10…Sawmills 12:00…Nyamandhlovu 12:29.

In Bulawayo excited crowds thronged the race course which was to be used

as a landing ground. Earlier the authorities had given warning by gun

and hooter that the aircraft was on its way. At 12:40 a speck in the sky

towards the north-west heralded the approach of “Silver Queen II” and a

few minutes later she touched down smoothly on the grass; the first

plane to land on the soil of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

Formal addresses of welcome were then read by Mayor James Cowden and

Acting Town Clerk F. Fitch, after which the party proceeded to the Grand

Hotel for a civic luncheon.

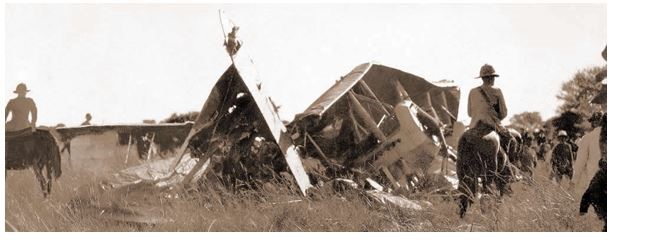

Next morning after the engines had been warmed up; “Silver Queen II”

taxied to the down-wind end of the field and commenced to take off for

South Africa. The Bulawayo Chronicle of Friday, March 5th 1920, gave the

following account of subsequent events: “The aircraft ran across the

cleared space and…lifted into the air only a few yards from the tangled

bush beyond the field. There were gasps of relief from the watchers and

then a delighted cheer. But it soon became evident that…all was not

well. Heading towards Hillside…only a few yards above the bush…she

disappeared from view. Apprehensions grew when the engines became

silent.”

“Some started running towards the Matsheumhlope River…others rushed to

cars and vehicles…motors scurried along tracks on the commonage between

South Suburbs and Hillside. Then (the first to reach the scene) saw the

wreck of the aircraft in the bush beyond the river. Both officers were

dishevelled and severely shaken, but not seriously injured, while the

mechanics sustained minor bruises.”

The dejected crew returned to their hotel, where they soon began to

receive messages of sympathy from far and wide. The most welcome of

these would have been the telegram from General J.C. Smuts advising them

that another aircraft would soon be on its way from Pretoria.

The replacement aircraft was a DH9 of the South African Defence Force

which arrived on Tuesday March 16th. Next morning the two pilots took

off on the final stage of the journey. A strike of rail and postal

workers was taking place at the time and Mr R. Lanning, Native

Commissioner at Plumtree asked Lieut-Col. Van Ryneveld to drop a few

copies of the Bulawayo Chronicle. This was agreed to and as the aircraft

swopped low over Plumtree School, the papers were dropped to Mr Lanning.

It is reported that one of them was endorsed by him and is now in the

National Archives.

The flight of van Ryneveld and Brand from Bulawayo to Cape Town was

relatively uneventful and they landed on Saturday March 20th, 1920, the

first men to fly from England to the Cape, for which achievement both

were later knighted. Sir Pierre van Ryneveld become Chief of the General

Staff, Union Defence Forces and retired to his farm near Pretoria in

1949 and died in 1972. Sir Quinton Brand, after a distinguished career

in the RAF where he achieved the rank of Air Vice-Marshall after a very

distinguished war records in both World Wars, came to Rhodesia, where he

died in 1968.